Index of Impressions: R M Willcocks, The Postal History of Great Britain and Ireland, privately printed, 1972

I purchased R M Willcocks’ The Postal History of Great Britain and Ireland on Wednesday, 23 rd September, 2015 at the Ealing (West London) Oxfam Bookshop. A small, navy-blue hardback of only eighty pages, the price was £3.99, and its condition very good. Being in effect a catalogue assembled to aid collectors of unusual postal markings, the volume is somewhat specialist in content and tone. It was apparently privately published in 1972. The expression “Woods of Perth” may be the printer’s name, its location, or both these things at once. An undated pamphlet obtained from the same shop earlier in 2015, Povey and Whitney’s The Postal History of the Manx Electric Railway, is similarly cryptic as to its origin, but echoes Willcocks in documenting obscure aspects of the UK postal system. But while the longer work includes several hundred images of labels or signs, in the Manx booklet are to be found only a handful of “Snaefell Cachets”, diamond-shaped rubber stamps recording a specific location and date.

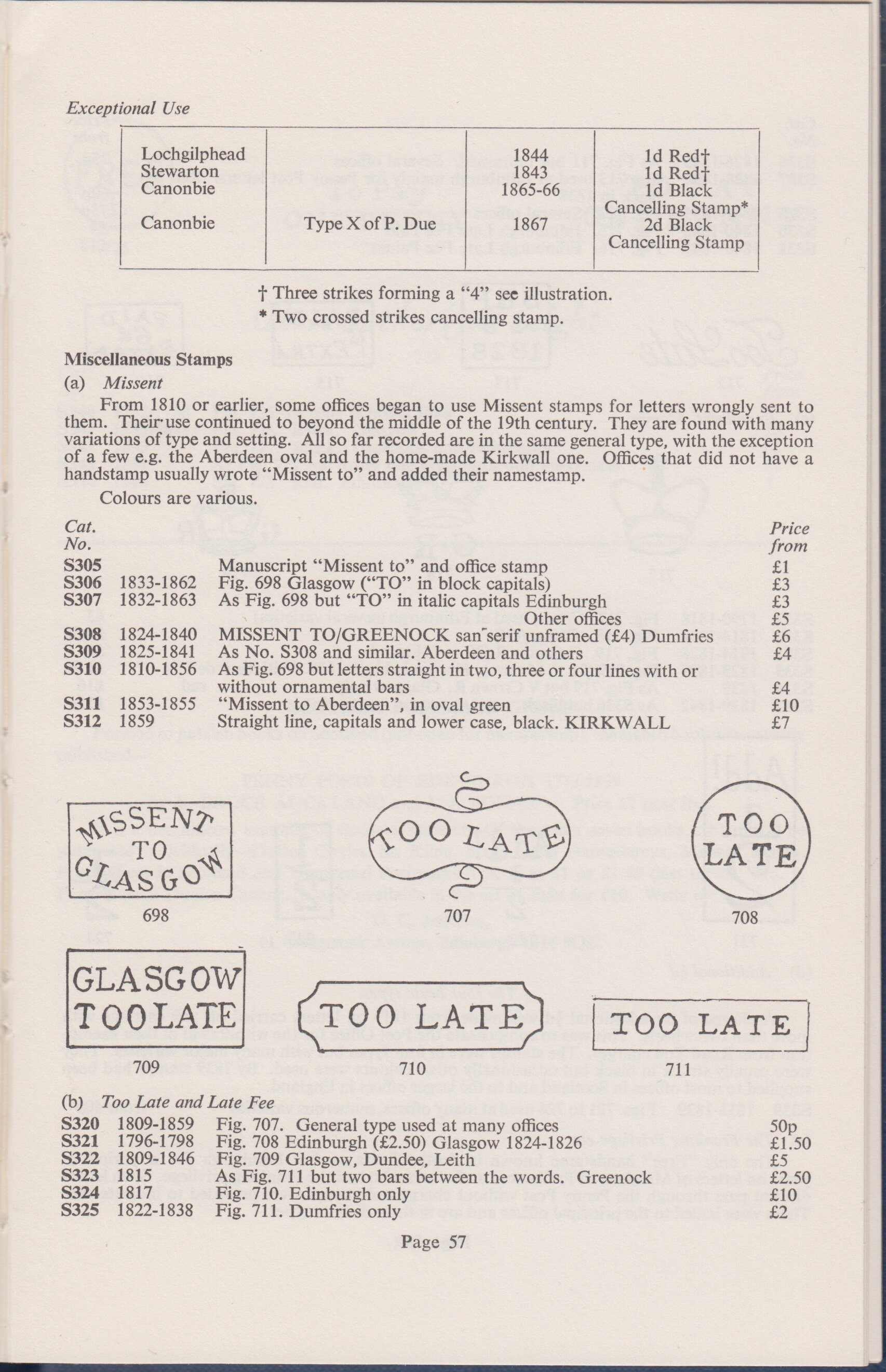

My interest in the book has little to do with the practical function of the franks scattered through Willcocks’ guide. I’m not too concerned that an item entered the mail-stream via the “LIBBERTON PENNY POST”, was “MISSENT-TO LEICESTER”, “RETD FROM WORTHING”, made it “UNPAID TO KIRKCALDY”, or arrived at its destination “TOO LATE”, “TOO LATE”, “TOO LATE”. What is engaging, however, is the provocative oddness of many of the handstamps this book contains: “AP 21”, “JY 7”, “DE 9” and “JA 16” are very likely dates, but they could equally be competition scores or personalised instructions. What exactly might be meant by “B MY 21”, “DON F ARM. DANGLETERRE”, “LASS WADE”, “GRAPE STATIONER”, “FREE E”, or “A -LONE”? Was “MARY STREET PENNY POST” a one-woman delivery service or a compact postal zone? And why is it that someone should so emphatically “Add! ½”?

A typical page from the ‘The Postal History of GreatBritain and Ireland’

Although I am mostly unable to grasp its esoteric terms, this guidebook will be, for its intended reader, a most helpful vade mecum. The province of the philatelist is a specialist discourse, and those unfamiliar with what students of linguistics would call its idiolect or subcultural code must either remain completely outside it, or, conversely, open it up to other kinds of account. There are hundreds of examples of postal markings here: numbers and letters, but also stars, crowns, circles, triangles, oblongs, squiggles, zig-zags and ellipses are scattered through the book in close proximity to the text. The latter asserts its own mysterious beauty, as a few short extracts will show:

“The following F stamps occur dated and undated, dated usually earlier.” (P. 40)

“Type X of P. Due” “Type W thin curl” (P. 56)

“Missent to Aberdeen”, in oval green” (P. 57). (This reads like something snipped off from an Emily Dickinson poem).

“Superb strikes of many are very difficult indeed to obtain, especially the various “Mermaids”.” (P. 60).

“In 1836 this was reduced to 2/6 plus postage. From 1820 stamps as Fig. 357 occur in red (shades) or black, with two types of crown (£45): Fig. 358 was 1836-71 (before 1845 £20, later red £7, other colours £15). It also occurs sanserif, and indications are that one or two may have been sent to Continental T.P.O.s. Fig. 359 is known in 1827-8 on Registered letters without Fig.357, and may replace it (£75).” (Pp. 38-39). (This passage is particularly obtuse).

Finally, we are told on p. 22 that “The Postmaster seems to have been an individualist who disliked the issued stamps, so used some of his own design, many in attractive shades of purple...[forming] a most attractive group to collect.”

Peter Suchin