The afterlife of glitter

Velvet Goldmine, Todd Haynes’ self proclaimed ‘glam rock Citizen Kane’ is 24 this year. Released in 1998, it opens with the title card instructing us to play it at maximum volume. And with a soundtrack this good, you wouldn’t dream of doing anything else.

The film begins by guiding us through an imagined glam rock dynasty: an emerald pin is bestowed upon an infant Oscar Wilde by a glittering spaceship, and, through the hands of time, and the enigmatic Jack Fairy (Micko Westmoreland), passed down to Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers): the faux-Bowie glam idol around whom our plot swirls. Despite the evident similarities in Slade’s career - from suited mod, to long auburn hair and flowing dresses to bejewelled alien alter egos - this is not a biopic about David Bowie. Firstly because it couldn’t be -Bowie refused to allow his music to be used in the film - but primarily because this isn’t a biopic at all, and has no interest in definitive notions of truth. This is filmmaking of another distinct genre: the genre of glam rock itself.

Our protagonist, Arthur, (Christian Bale), is a former glam fanboy, now journalist in a grey 1984 New York (filmed in the most New York-esque London boroughs that budget would allow). Arthur is attempting to discover just what happened when Slade’s alter ego, and the Ziggy-adjacent hero of his teenage years - Maxwell Demon - committed performative suicide, on the day the music of his youth died. In his investigations he runs through the figures in Slade’s eclectic inner circle: his Iggy Pop/Lou Reed style lover Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor), Angie Bowie allied ex-wife Mandy (Toni Collette) and Jerry Devine (Eddie Izzard), Slade’s former manager, to unravel the story of his own adolescence, Slade’s career, and the inextricable nature of their tangled lives.

It is a film packed to the gills with the visual language of glam: glitter, platforms, sharp zooms, cuts, dream-glow vaseline-lens musical numbers and a score dripping in musical talent, but Haynes has stated on many occasions the filming process was a difficult one, tight on money and time, fraught with tension and doubt as to whether it would live up to its ambitious pitch and precise script. The difficulty of the creative process notwithstanding, its performances, some of which, like Meyers, were breakout roles, and inimitable vision have elevated Velvet Goldmine to a much deserved cinematic status. Its shoestring nature, if anything, is what cements it as a cult classic - too high of a budget and one risks losing the, for want of a less ironic term, ‘authenticity’ required to capture such a counterculture onscreen.

Watching for the first time, as a 15 year old girl that wanted to be a boy that looked like a girl, glam rock felt like a space wide open with possibility. Glam is inherently adolescent, it is a genre of sexual discovery and theatrical play: it is a genre that attempts to throw gender to the wind, whilst inevitably becoming obsessed with the performance of it. It is a genre of sex, appearance, costume, identity and desire; the true and, more importantly, the false. Imagination and adolescence are the crux of Slade’s resonance with his audience. The film’s credits, to Needles In The Camel’s Eye, show gangs of teenagers in their platform boots, touching up their lipstick in storefront windows. In one scene, two schoolgirls enact Slade and Wild’s love affair with dolls on their bedroom floor; in another, Bale’s Arthur touches himself to a picture of Slade on the album sleeve and images of Wild and Slade kissing splashed across the front of newspapers, as the guitars on Slade’s album crescendo to psychosexual heights. Of these scenes, Haynes says, “There’s something palpable about intercutting the public sexuality of the rock stars with the very private, unknown sexuality of the consumer, and how one directly affects the other,” and Arthur’s rooftop tryst with Curt Wild is the meeting of these two concepts, the merging of the imagined idol and the very real sexual awakening they are responsible for into one. As they fuck:

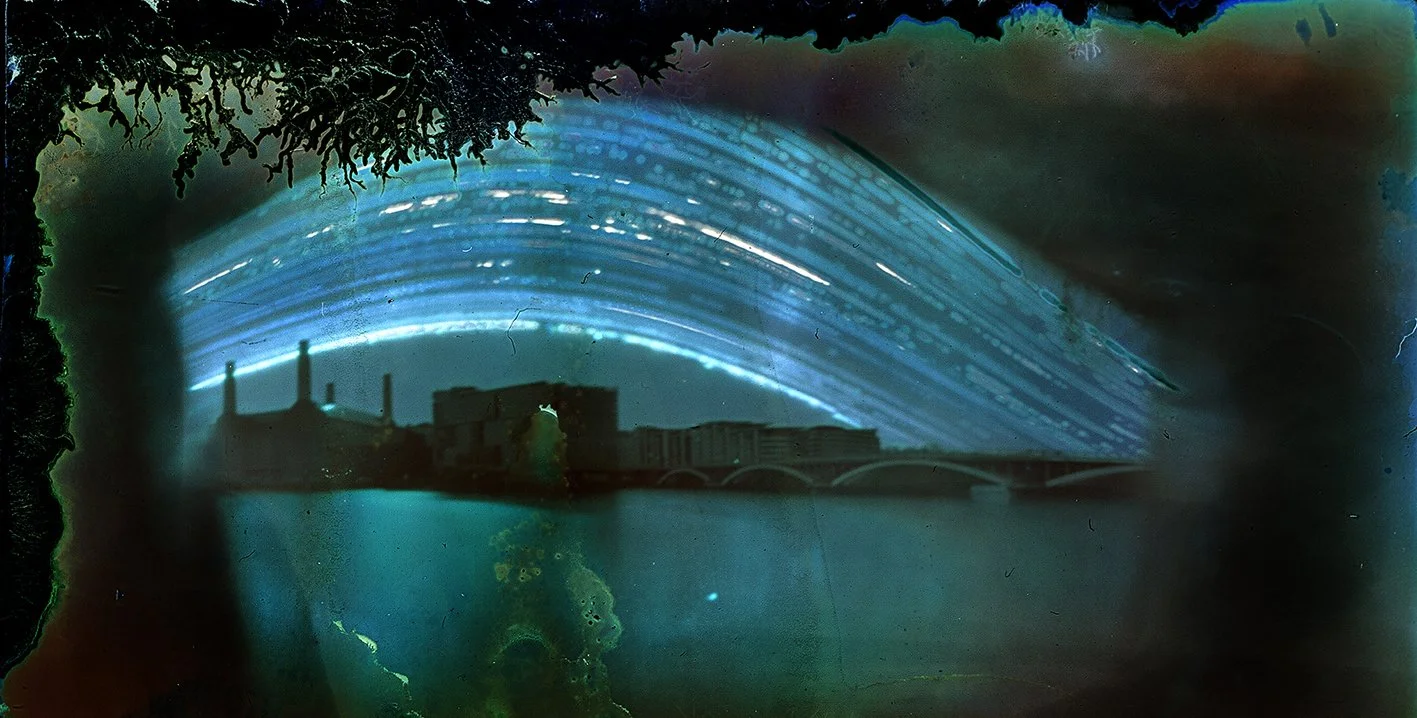

A luminous spacecraft, like the one that passed over Old Dublin. It swirls over London with a thunderous boom–

– and vanishes.

All that remains is a sky full of glitterdust.

When Wild and Arthur meet years later, however, this night on the rooftop appears to have been forgotten by Wild. Velvet Goldmine is as much about the death of glam, than glam itself - about its transience, and the inevitable impermanence of a genre centred on the performed. For Arthur, glam exists in contrast with the drab corporate nature of his adult life, the narrative frame of remembering allowing it to exist in an elevated, fantastical position. His adolescent years are over, the culmination of them, his night with Wild, taking place the same night as the Death of Glitter tribute concert to Slade’s passing.

For Arthur, this is a funeral for his teenage years, for Slade Maxwell Demon's death is the debatably ‘necessary’ reinvention of the artist as they enter a new era, and speaks of the need to kill one’s artistic self in order to start anew without preconceptions. Despite, or perhaps because of Bowie’s absence from the film, it is impossible to not draw parallels with the figures. The grieving of Slade’s fans for Maxwell Demon is undeniably that of a nation for Ziggy Stardust, and Slade’s new persona, Tommy Stone, is a cynical view of the grown up, corporate Bowie that came with the 1980s and the Thin White Duke. Haynes chose the year 1984 for the frame narrative as the George Orwell novel served as the inspiration for Bowie’s Diamond Dogs, as he says “1984 was already a focus of future doom fantasies within glam rock itself”. Tommy Stone has none of the androgyny of Maxwell Demon, he is a hypermasculine, suited and distinctly corporate figure; a sellout who publicly praises the US president and seems to betray and deny glam’s appeal: its queerness. Furthermore, Slade attempts to transform into Tommy Stone without anyone noticing, creating for himself a character devoid of any of the artistic lineage afforded by the glam royal line of Wilde and Jack Fairy. It is impossible to define oneself outside of the defining frame of others. Without the tightlaced culture that he was countering, what would Slade be? Without the legacy of Maxwell Demon, what is Tommy Stone?

CURT

A real artist creates beautiful things and… puts nothing of his own life into them. Okay?

ARTHUR

Is that what you did?

CURT

No. We set out to change the world and ended up… just changing ourselves.

ARTHUR

What’s wrong with that?

CURT

Nothing. If you don’t look at the world.

In Velvet Goldmine, Haynes seems to imply that the death of glam means the death of glittering adolescence, and in Slade/Tommy, the birth of a new, less interesting reaction to an existing reactionary counterculture. But nothing in glam is permanent, nor to be taken as truth. The emerald brooch of inherited glamour, which in the opening is passed through Oscar Wilde, to Jack Fairy, to Slade, ends up with Arthur, slipped to him in his beer by Curt Wild, in some remembrance of the night they shared. The final scene plays out to the refrain of “Here’s looking at you, kid”, and as Haynes himself has said “that pin will keep moving through time and be picked up and passed on in many different ways”. At Velvet Goldmine’s close, the legacy of performance - of glam - is left with one who, upon first glance, appears to have outgrown his teenage years, but it could be picked up by any of us. And maybe, like Arthur, we’ve all just pretended to grow up.

By Eden Peppercorn

All quotes are taken from Superstardust: Talking Glam with Todd Haynes, by Oren Moverman, as published in the introduction to the Velvet Goldmine screenplay, 1998.